The Great Scandinavian Baking Book

The revelation of my grandmother’s scrawled recipe for lefse, allegedly passed down for generations, was that its key ingredient was Betty Crocker Potato Buds. Known variously as dried potatoes and instant potatoes and a staple of camping trips, they were invented in 1952, when my grandmother was 42, so counting me and my mom, I think we can surmise that it was passed down exactly twice.

Lefse is a Norwegian crepe, traditionally made from potatoes, a little heavy cream, and just enough flour to bring it all together. Rolled out from small balls to a tortilla-like flattened disk, the lefse is cooked on one side till it has brown blisters, then flipped till the same thing happens on the other side. As a child, I thought it looked like a moldy dishrag. But warm from the grill, buttered, and sprinkled with cinnamon sugar, it was heavenly.

I never tried my grandmother’s recipe, which my mother made every Christmas to serve with platters of cheese or with vegetable soup. But I had tried other recipes that used boiled potatoes, not dried, and it never worked. The good news was that a bad piece of lefse is still a fine accompaniment for smoked salmon and a little sour cream, for watercress in a garlicky lemon dressing and parmesan shavings, for leftover Christmas ham, with dill and mustard and if you’re lucky, some Jarlsberg cheese.

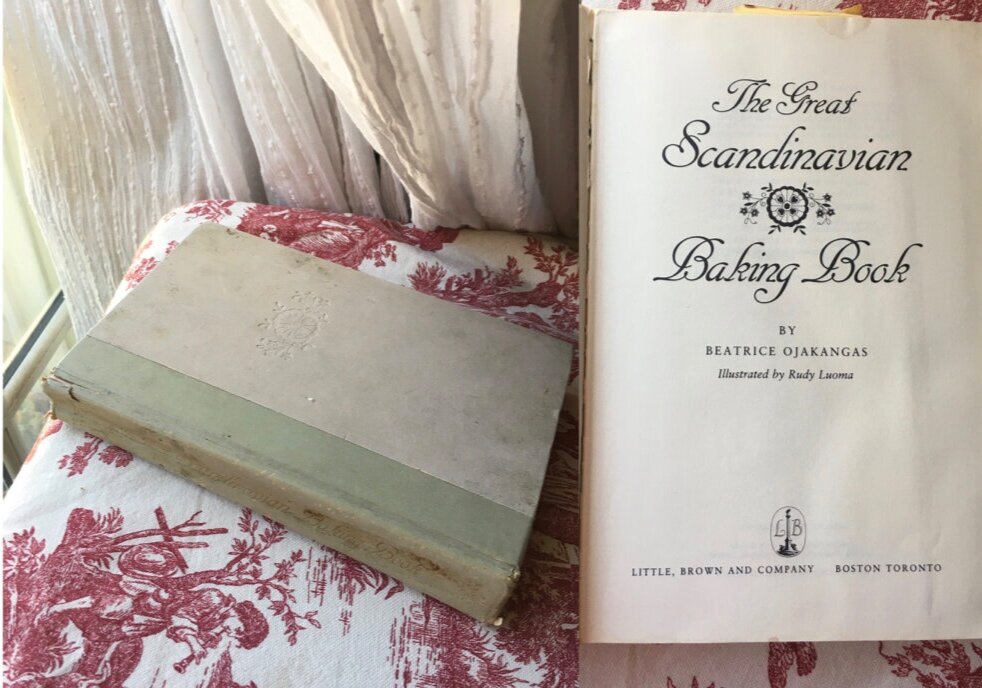

Success came when I came across a copy of The Great Scandinavian Baking Book by Beatrice Ojakangas (Little, Brown, 1988), who knows more about flatbreads and butter cookies that anyone I’ve ever met, read, or listened to. In her generous instructions for making lefse, she lets slip that every Norwegian baker knows to leave the potato dough in the refrigerator overnight to rest. With that tip, I was ready to make lefse once a week at our tea room in the East Village, to use instead of sliced bread for cucumber sandwiches.

Ms. Ojakangas, writing about Rågsiktlimpör, a sweet holiday rye bread scented with anise and orange and molasses, tells us why overnight proofing helps the flavors blend, but fails to mention that you simply lose your mind from the scent while it’s baking. She taught me to have a light hand when mixing butter cookies so that the crumb would be delicate. Vanillekranse, or Danish vanilla wreaths, are the cookies we know from familiar blue tins found in drugstores and supermarkets all year round. Her wry observation: “Cookies that have been baked months ago and shipped long distances hardly resemble the freshly baked product.”

Amen. This book is my baking bible. In it I found the recipe for gingerbread houses that reminded me of a beloved piano teacher’s cookies, with an orange scent. The author knows how to turn kaffeeklatsch into a four-course meal. Her notes on the origins of recipes, on her little discoveries in various countries, e.g., why black bread is shaped into an “O” (because then all the loaves can be strung up on a rope, away from the mice all winter), make this an armchair delight. Still, it’s hard not to stand up from that chair and start rustling around in the cupboard, checking for ingredients. If you have a stick of butter, delicately scented cookies are only a few minutes away, and Ojakangas is the only tour guide you’ll need.